《기울인 몸들: 서로의 취약함이 만날 때》 접근성 기획에 대한 기록 Making an Exhibition a Little Different

A Record of Accessibility Planning for Looking After Each Other

‘모두를 위한 ◯◯’이라고 말하려는 사람은 누구든 냉소와 맞닥뜨릴 준비를 해야 할 것이다. ‘모두를 위한 미술관’이라고 말할 때도 마찬가지다. 모든 사람이 미술을 즐겨야 한다거나 모든 사람이 같은 취향을 가져야 한다는 뜻은 아니다. 이 표현은 미술관이 공공의 공간으로서 당위성을 확보하고 있는지를 묻는다. 최근 문화예술계에서 활발하게 논의되고 있는 ‘접근성’이라는 의제는 이 수사의 선두에 있다.

프랑스 혁명기 특권층이 독점하던 미술품을 시민에게 개방한 그 탄생의 순간부터 ‘모두를 위한’이라는 강령은 공공미술관이 마땅히 따라야 할 윤리로 작동해왔다. 하지만 근본적으로 이런 의문이 생길 수 있다. 아름다움을 추구하는 것과 올바름을 추구하는 것이 정말로 합치될 수 있을까? 미술관은 첨단의 문화를 선보이는 장소다. 때로는 옳고 그름의 문제를 넘어설 수 있다는 점이 예술에 전복적 힘을 부여하는 것도 사실이다. 하지만 설화 속 에밀레종 소리가 아무리 청아하다고 한들 한 아이의 생명을 희생할 정당한 근거가 될까? 질문은 꼬리를 물고 이어진다.

조금 더 실질적인 차원에서 전시는 재화로서 ‘문화적 가치’를 사회에 내놓는 일이다. 오늘날 우리 사회의 다른 많은 일과 마찬가지로 전시를 만드는 일은 가능한 적은 자본을 투여하고 가급적 높은 가치를 회수한다는 셈법을 따른다. 이윤으로서의 문화적 가치 창출이라는 목적을 극단적인 수준으로 추구할 때, 윤리적 결함은 그리 중요한 문제가 되지 못할 수도 있다는 뜻이다. 예컨대, 적은 예산으로 거대한 전시 공간을 조성하기 위해 매일 홀로 페인트를 칠하는 이주민 노동자가 있을 수 있다. 완성도 높은 도록을 만들기 위해서라면 중증장애인 업체보다는 숙련된 인쇄업체를 선택할 수 있다. 어떤 관객에게는 세심하게 동선이 고려된 VIP 투어가 제공되지만, 휠체어를 탄 다른 관객이 언제나 뒷길로 입장한다는 사실에는 무심할 수 있다. 건강을 잃고 마음을 다쳐 업계를 떠날 수밖에 없었던 동료들을 안타까워하면서도, 산처럼 쌓인 일감을 두고 생활을 돌보러 나서는 팀원에게 애꿎은 원망이 치솟기도 한다. 비록 전시가 주장하는 바가 그 정반대일지라도. 부끄럽지만 이 일에 본인도 연루되어 있음을 고백한다.

혼자였다면 입에 들러붙은 회의감에 그치고 말았을 것이다. 다행히 여정을 함께해 줄 길잡이가 있었다. 전시 개발 단계부터 생각을 나누며 본 전시의 접근성을 기획한 ‘조금다른 주식회사’는 다음과 같은 관점에서 전시와 접근성을 함께 발전시켜 볼 것을 제안했다.

접근성의 본질은 단순히 기능적으로 접근성을 구현하는 것이 아니라, ‘경계와 무관하게 콘텐츠를 즐기는 것’에 있습니다. 기능적 편의를 기본으로 하되 접근성이 미학적인 창작의 시도이기도 하다는 점을 인식합니다.

접근성을 높이기 위한 방법이 그 자체로 감상과 향유의 대상이 될 수 있다면, 서로 다른 두 목표가 어느 지점에서 만날 수도 있지 않을까? 매체의 변화는 예술적 표현과 연결되고, 미감은 우리를 모으거나 갈라놓기도 하니 말이다. 우리는 접근성 장치가 접근성의 향상이라는 기능과 더불어 그 자체로도 향유의 대상이 될 수 있는 방법을 모색해 보기로 했다.

나아가 ‘조금다른 주식회사’는 단번에 모두 이루어낼 수 없을지라도, 한계를 받아들이고 지향점을 공유하는 계기로서 전시의 역할을 다시 상기시켜 주었다.

‘모두를 위한 미술관’은 아이러니하게도 미술관이 가진 한계를 인식하는 것으로부터 시작되어야 합니다. 현재의 미술관은 ‘모두’를 위한 곳이 아님을, 그리고 우리가 가진 시간과 자원을 통해 미술관이 가진 장벽을 완벽하게 허물수 없음을 인정하고, 그럼에도 우리가 ‘모두를 위한 미술관’이라는 목표를 가지고 나아가는 이유를 함께 공유하는 것입니다.

완벽하게 해내야 한다는 강박, 예기치 못한 비난을 피하고 싶다는 두려움, 헛수고를 할 바에야 안주하고 싶다는 게으른 마음을 조금이라도 넘어설 수 있었던 건 함께 버텨 준 동료가 있었기 때문이다.

이렇듯 《기울인 몸들: 서로의 취약함이 만날 때》는 서로 다른 관점을 가진 두 팀이 서로를 이해하고, 타협하고, 북돋우며 만들어졌다. 이 글은 그 과정을 나누기 위해 쓰였다. 모든 이야기를 담을 수 없었기에, 활용하면서도 향유할 수 있는 접근성 장치를 모색한다는 목표를 둘러싼 고민과 현실적 조건 사이에서 일어난 갈등과 협상을 잘 보여줄 수 있는 점자블록, 쉬운 글, 음성해설의 세 가지 사례를 택했다. 결국 실패로 돌아갈지도 모를 이 과정을 기록하려는 데 다른 이유는 없다. 이 전시가 초대받지 못했던 누군가와 함께하고자 했던 수많은 이들의 시도에 빚지고 있듯, 이 시도를 이어 나갈 누군가가 한 걸음 더 나아간 질문을 할 수 있도록 돕기 위함이다.

새로운 규칙을 가진 점자블록

점자블록 설치 여부부터 논쟁거리였다. 시각장애인의 자율적인 관람을 가능하게 해보자는 생각은 근사하면서도 터무니없게 들렸다. 게다가 전시장 바깥 로비 공간까지 점자블록을 설치하기에는 예산이 부족했다. 또 가까운 지하철역이나 버스 정류장에서부터 미술관까지 시각장애인이 혼자 오는 것이 가능한가 하면 그것도 아니었다. 보여주기식 전시라는 비난이 귓가에 선하게 들려왔다. 어쩌면 두려운 마음에, 점자블록을 설치하지 않을 핑계를 찾고 있었는지도 모른다.

전시 기획팀: 물론 전시를 준비하면서 관람 동선을 고려하기는 하지만, 어디까지나 관람은 자율적인 것인데요. 점자블록을 누군가 선택할 수 있는 모든 동선에 놓을 수 있는 것이 아니라면, 결국 관람의 자율성을 제한하는 결과가 되지는 않을까요?

접근성 기획팀: 하지만 작품에 완전히 접근할 수 없는 것보다는 작품에 제한적으로라도 접근할 수 있는 편이 낫지 않나요?

명확한 답변이었다. 전시 기획팀은 공간 디자이너와 함께 점자블록을 설치할 방안을 찾기 시작했다. 그리고 적어도 이번 전시가 열리는 전시장 안에서만큼은 시각장애인들이 독립적으로 관람할 수 있는 환경을 조성하는 것을 목표로 하기로 했다.

점자블록을 설치하려니 그 모양과 형태에 대한 질문도 생겨났다. 기왕 미술관에 설치되는 것이라면, 점자블록도 예술적 실험의 대상이 될 수 있지 않느냐는 이유에서였다.

전시 기획팀: 점자블록은 꼭 노란색이나 흰색만 사용해야 하나요? 점자블록의 모양은 점과 선으로 정해져 있나요? 다른 색깔이나 모양을 사용하면 안 되나요?

접근성 기획팀: 점자블록의 제1원칙은 시각장애인의 ‘접근성’을 보장하는 것입니다. 새로운 시도를 해보는 것은 좋지만, 그 시도가 점자블록이 가진 기본적인 존재 이유와 기능을 해쳐서는 안 됩니다. 따라서 아래와 같은 원칙에 따라 생각을 확장했으면 합니다.

- 점형과 선형이 가진 고유한 역할을 변형시키지 않습니다.

- 점자블록의 색상은 기존 바닥의 색상과 명확히 대비되도록 합니다.

- 점자블록의 설치 각도, 배치 방법, 규정 등을 벗어나지 않도록 합니다.

이런 안내에 따라 전시에서는 일반적으로 활용되는 점자블록의 색상과 모양, 설치의 방식을 준수하여 점자블록을 설치하였다.

‘조금다른 주식회사’는 점자블록의 기본적인 목표와 규칙을 알려주는 것에 그치지 않고, 전시 관람의 핵심 요소인 ‘작품’의 위치를 표현할 색다른 방법을 고안할 것을 제안했다. 그리고 2023년 페루 리마에서 정류장 번호를 표시하기 위한 점자블록의 모양을 새롭게 고안하고 적용했던 사례를 이야기해 주었다. 페루의 사례를 참고해 전시 기획팀은 공간 디자이너와 함께 점형과 선형을 조합하여 작품을 표현할 점자블록의 형태를 고안했다. 드디어 점자블록의 규칙에서 벗어날 기회가 생겼는데 왜 다시 점형과 선형이었을까? 완전히 다른 모양의 점자블록을 제작할 경우 상당한 비용이 든다는 현실적인 이유에서였다.

-

선형 블록

흰색세로로 긴 3개의 돌출된 선이 나란히 있습니다. 선이 향하는 방향을 따라 이동해도 괜찮다는 뜻의 블록입니다.

-

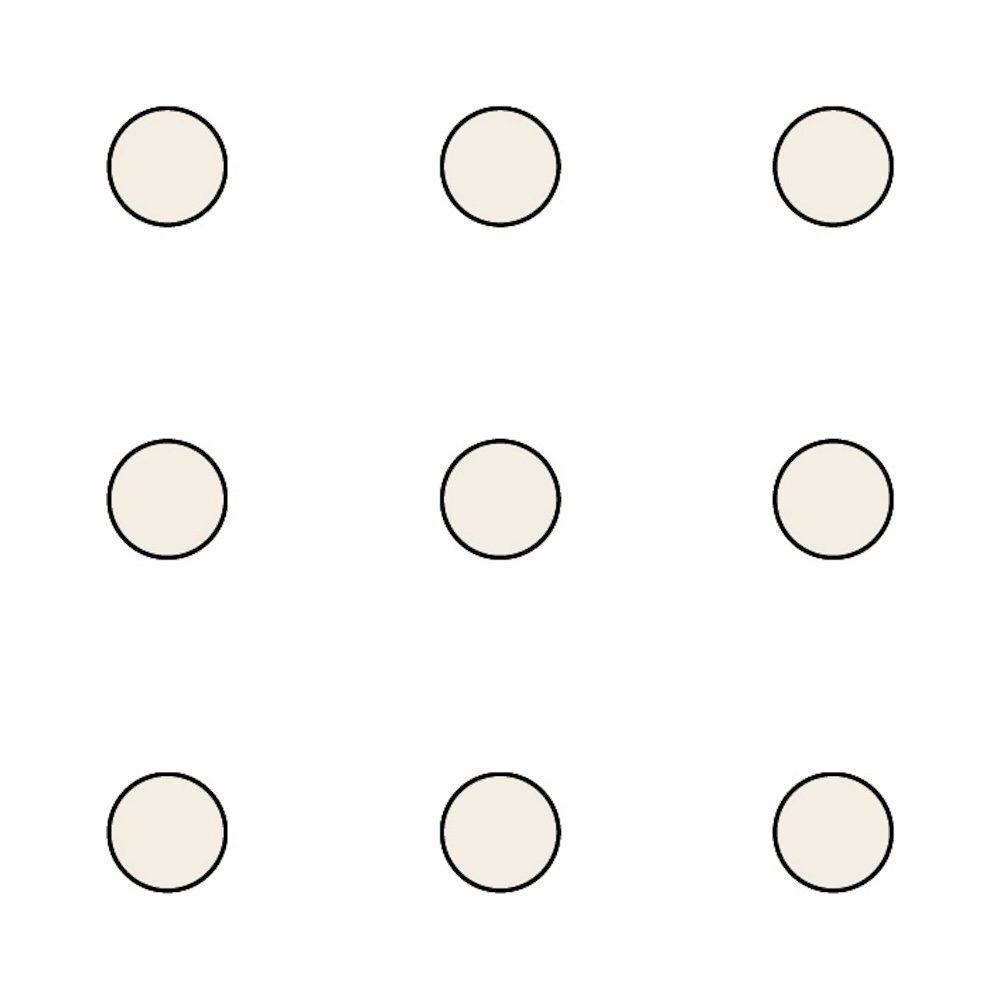

점형 블록

흰색돌출된 원형 점 9개가 있습니다. 앞에 각종 벽, 출입구의 위치, 길의 끝 등이 있으므로 정지해야 한다는 뜻의 블록입니다.

-

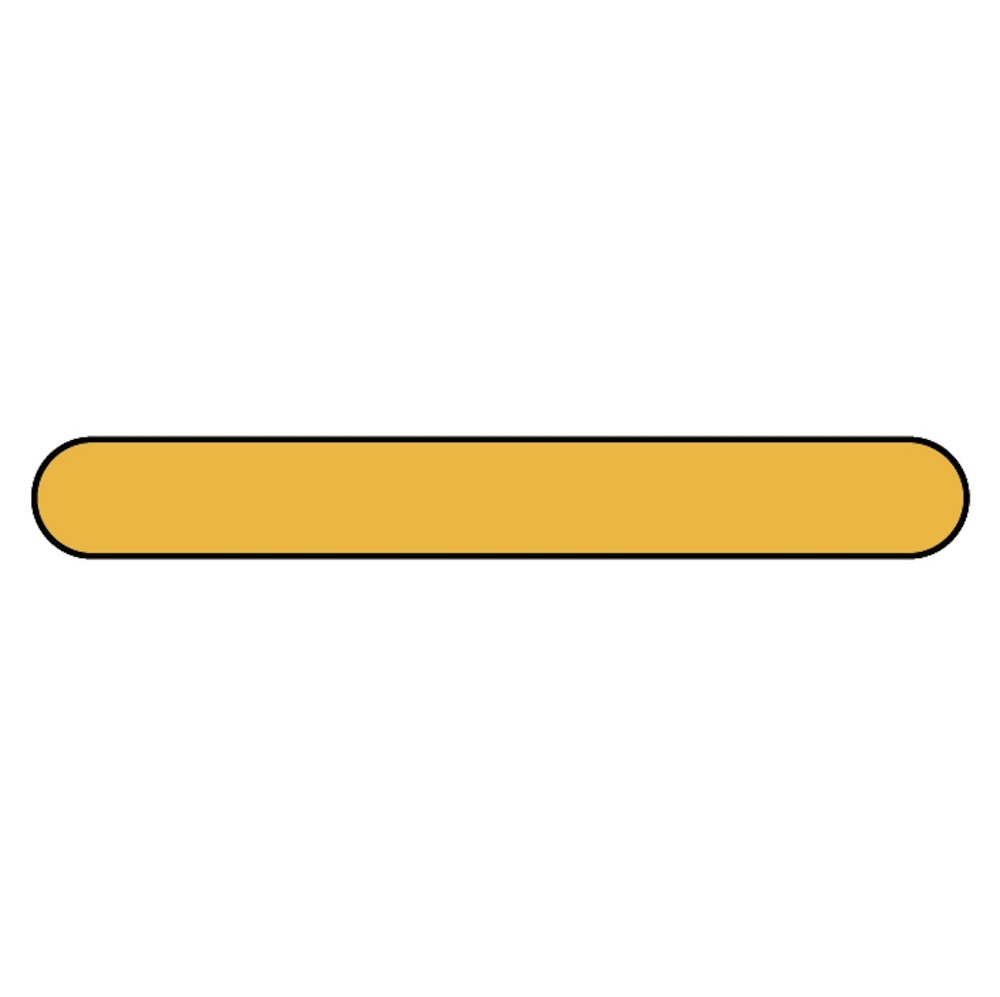

작품 블록

노란색중앙에 가로로 긴 1개의 돌출된 선이 있습니다. 해당 점자블록이 있는 곳 앞에 작품이 있다는 뜻의 블록입니다.

-

대화형 음성해설 작품 블록

노란색기존 작품 블록처럼 가로로 긴 1개의 돌출된 선을 중심으로 각 모서리에 돌출된 원형 점 4개가 있습니다. 대화형 음성해설이 포함된 작품이 있다는 뜻의 블록입니다.

‘쉬운’ 글 혹은 쉬운 ‘전시’ 글

전시의 모든 글을 ‘쉬운 글’로 작성하자는 데에는 이견이 없었다. 때로 읽기 어렵다 못해 독백에 그치는 전시를 보며 허망함을 느끼기도 했고, 단순한 언어를 쌓아 복잡한 메시지를 전달하는 일도 가능하다고 믿기 때문이기도 했다. 그러나 쉬운 글에서 ‘쉬운’의 의미는 문장의 난이도에 대한 견해를 넘어서는 것이었다. 누구도 정보에서 배제되어서는 안 된다는, ‘알 권리’에 대한 태도를 담고 있어서다. 이런 이해를 바탕으로 이번 전시에서는 쉬운 글을 미술관에서 작성한 해제와 병치하지 않고 단독으로 제시하기로 했다. 미술관에서 작성한 글을 토대로 ‘조금다른 주식회사’와 최서우 작가가 쉬운 글로 번역 및 작성하고, 작가와 발달장애인 자문단의 검토를 받았다. 유니버설 폰트와 큰 글자로 가독성을 높인 것은 물론이다.

문제는 ‘쉬운’ 글에 대한 견해 차이였다. 예컨대 전시 서문의 마지막 부분은 다음과 같이 수정되었다.

전시 기획팀: 전시는 다양한 몸을 있는 그대로 바라보는 방법, 서로 다른 몸이 함께 살아가는 방법, 서로에게 기대어 있는 존재로서의 우리를 보여준다. 그 모습이 아름답게 보인다면, 그때 우리의 품이 조금 더 넓어질 것이라 기대하면서.

접근성 기획팀: 전시는 몸을 있는 그대로 바라보고, 다양한 몸과 더불어 살아가고, 기댈 수 있는 서로가 되는 방법을 전한다.

마지막까지 이 문장을 어떻게 표현할 수 있을지 깊이 고민했다. 기존 글이 어렵다고 말할 수는 없었지만, 곱씹어 해석해야 그 의미를 가늠해 볼 수 있는 문장이라는 점에서 분명한 문구라고 볼 수 없었다. 하지만 부드러운 방식으로 에둘러 읽는 사람에게 사유의 계기를 제공하려는 의도에서 작성된 문구였기에 삭제한다는 결정에 아쉬울 수밖에 없었다.

그러고 나니 쉬운 글에 대한 고민이 밀려왔다. 전시 또는 작품에 담긴 복합적인 맥락과 의도는 얼마나 간단명료한 언어로 표현될 수 있을까? 아름다움을 말하는 장소인 미술관에서 제공하는 글에 말맛을 고려하지 않는다면 바람직한가? 혹은 사유를 불러일으키는 장소인 미술관에서 제시하는 글에 해석 또는 질문의 여지를 남기지 않는 것이 적절한가? 미술관이라면 모름지기 미감도 정보 아닌가? 윤리적인 관점에서 보더라도, 쉬운 글을 요구하는 사람들에게 추론 능력이 결여되어 있다거나 말맛을 느낄 수 없다고 생각하는 것이 올바른가? 쉽고도 아름다운 글이라는 이상은 존재했지만, 그에 다다르는 길은 요원했다.

쏟아지는 질문에 ‘조금다른 주식회사’는 쉬운 글에서조차 배제되는 이들이 있어서는 안 된다는 방향성을 다시 떠올리게 해주었다. 쉬운 정보를 요구하는 사람들에게 어떤 능력이 없어서가 아니라, 그들 중 유추에 어려움을 느끼는 이들도 분명 존재하기 때문이었다. 다만 미술관에서 작성한 원문도 가급적 쉽게 작성되었기 때문에, 아래 두 가지 방향 중 선택할 것을 제안했다.

접근성 기획팀:

원문을 최대한 살리고, 어려운 단어와 긴 문장을 분절한다. = 쉬운 ‘전시’ 글. 쉬운 글의 방향성을 살리되, 닫혀 있는 문장 구조 사이에 중요한 질문(사유, 유추 목적) 형태의 문장을 추가한다. = ‘쉬운’ 전시 글

본 전시에서는 전시에 접근할 수 있는 권리의 확장이라는 목표 아래 두 번째 방향을 채택했다. 이후에도 논의는 계속되었다. 점잖게 당황을 표한 몇몇 작가들을 설득하는 동안, 여전히 어렵다는 발달장애인 검토 의견이 돌아왔다. 태도이자 입장으로서 쉬운 전시 글에 대한 고민은 앞으로도 지속될 것이다.

감상의 나눔으로서의 음성해설

한 사람 한 사람의 시각장애인 관객을 응대할 별도의 인원을 배치하기에는 예산이 모자랐다. 하지만 어떤 식으로든 작품에 대한 설명이 제공되어야 했다. 몇몇 작품을 선정해 음성해설을 준비할 수는 있었지만, 들려주는 방식이 문제였다. 위치 기반 애플리케이션을 이용하자니 센서 작동이 섬세하지 않았고, 더욱이 전시장에는 작품과 관객으로부터 비롯되는 다양한 소리가 존재할 터였다. 너무 많은 소리가 겹쳐 불쾌감을 가중할 가능성도 있었다. 그렇다고 해서 헤드폰이 완벽한 선택지도 아니었다. 헤드폰을 써야 한다는 사실 자체가 또 하나의 장벽이 되기 때문이었다. 음성해설이 그 자체로 감상할 만한 콘텐츠가 되어 시각장애인이 아닌 관객에게도 유의미한 감상의 도구가 될 수는 없을까? 시각장애인을 대상으로 마련될 음성해설은 도슨트를 대신하는 오디오가이드와 무엇이 달라야 할까?

이런 고민에서 출발해 ‘조금다른 주식회사’는 조금 특별한 방식의 음성해설 제작을 제안했다. 시각장애인을 포함한 2인이 짝을 이루어 작품에 대해 대화한 후 그 내용을 토대로 음성해설을 제작하자는 계획이었다. 이 계획에는 몇 가지 이점이 있었다. 먼저 실제 당사자의 입장에서 궁금한 내용을 파악하기에 용이했다. 둘째로, 개인의 감상을 경유하여 친근하면서도 생동감 있는 작품 설명을 제공할 수 있었다. 다만, 자칫 ‘작품 해설’이라는 목적과 무관한 사적 정보의 기술이 될 수도 있겠다는 우려를 수용하여, 작품과 무관한 정보는 제외하기로 방향을 잡았다. 외에도 이 음성해설에는 전시 공간의 인상, 냄새, 울림, 소리, 촉각, 경험의 순서 등 미술관에서 작품을 감상할 때 동반되는 다양한 요소들이 포함되었다. 미술관에서 작품을 감상할 때 시각에만 의존하지 않고 다양한 감각을 활용한다는 점을 강조하면서 시각장애인과 비시각장애인 모두 각자의 감상 경험을 공유할 수 있도록 하기 위함이었다. 시각장애인이더라도 저시력자의 경우 시각이 매우 중요한 감상 요소가 된다는 점까지 고려한다면, 감각 기관의 사용 방식에 따른 경험의 차이를 드러낼 수도 있었다. 다음은 예시로 작성된 음성해설의 일부다.

접근성 기획팀:

A: 작가 이름은 크리스틴 선 킴. 한번 검색해 볼게요. 크리스틴 선 킴 작가는 한국계 미국인이고 청각 장애를 갖고 태어났다고 하네요.

B: 아, 그래서 본인이 사용하는 언어인 수어를 재료로 예술 작품을 만드는 건가요?

A: 그런가 봐요. 그렇다면 결국 “수어를 하는 사람과 수어를 읽는 사람은 서로 손의 다른 면을 바라보고 있지만, 결국 그 뜻은 똑같이 통한다” 뭐 이런 메시지를 전하려고 했던 게 아닐까요?

B: 그럴 수도 있겠어요. 그러고 보면 점자는 평면에 인쇄된 것을 읽는 방식이니까 한 방향, 한 면으로만 읽을 수 있는데, 수어는 손이라는 신체를 사용하는 언어라서 여러 방향에서 읽는 게 가능하네요.

A: 오! 그렇게는 생각해본 적 없는데. 맞는 말씀이세요. 사실 저도 수어를 배워보고 싶다는 생각을 한 적 있었어요.

B: 그래요? 저는 점자를 익히는 데도 너무 시간이 오래 걸리고 힘들었어요. 어렸을 때부터 훈련 했으면 좀 나았을 텐데… 성인이 되고 나서 배우려니 참 어렵더라고구요.

가능한 한 객관적인 언어로 작품을 묘사, 해석, 평가하고자 하는 미술관의 해제와 이 음성해설은 분명 서로 다른 방향을 향하고 있다. 하지만 이 음성해설이 작품의 객관적 기술과 주관적 감상 사이 어디에 위치하든, 거기에 무언가 근본적인 아름다움이 있다고 느낀다. 왜인지는 명확하지 않다. 아마도 미술의 본령이 있다면 무언가 보는 데 근거하는 것이 아니라, 무언가 전하고 나누는 데 있기 때문이라고 짐작할 뿐이다.

‘접근성이 미학적인 창작의 시도’라는 문장은 일종의 자기 주문이기도 하다. 글을 읽은 사람들은 모두 눈치챘겠지만, 접근성 작업은 설득과 타협의 연속이다. ‘모두를 위한 미술관’이 되기 위해서는 먼저 ‘단 한 명을 위한 미술관’이 되어야 하기에, 숫자로는 증명할 수 없는 어떤 가치를 바라보고 쫓아야 한다. 정답이 없는 가치를 좇다 보니 그 이상에는 끝이 없고, 숫자로 증명할 수 없는 일은 의심받기 일쑤다.

완전한 이동의 자유를 보장할 수 없는데도 점자블록을 설치해야 하는가? 새로운 언어 체계를 가진 점자블록을 설치하는 것이 많은 예산을 투자할 만큼 시급하고 효과적인 일인가? 모두가 받아들일 만큼 쉬우면서도, 아름답고 말맛이 살아나는 글은 어떻게 작성할 수 있는가? 작가의 해설이 아닌 관객의 감상이 작품을 설명하는 역할을 수행할 수 있는가? 장애인 예매 과정에서 장애인은 본인의 장애를 ‘증명’해야 하는가? 이 모든 고민을 거치고도 여전히 배제되는 수많은 이들과 우리는 어떻게 이후를 이야기할 수 있을까?

수많은 질문과 담론들 사이에서, ‘접근성이 미학적인 창작의 시도이기도 하다’라는 문장은 동력을 주는 이정표가 되어준다. 이번 여정에 함께한 이들과 이 이정표가 가진 의미를 꽤나 치열하게 고민하고 열심히 쫓았다. 물론 그럼에도 여전히 정답을 찾지 못한 질문들도 있고(오히려 늘어난 것 같기도 하다), 여러 이유로 타협하게 된 순간도 있었다. 그러나 타협이 꼭 나쁘다고 생각하지는 않는다. ‘이번에는 여기까지’라는 말은 안일하게 느껴지더라도, 이후를 바라보고 지속 가능하게 만들어주는 쉼터의 역할을 하기도 한다. 이번만 하고 끝낼 게 아니기에, 부족했던 지점은 다음에 더 잘 해내고 싶다.

이번 《기울인 몸들: 서로의 취약함이 만날 때》에서 얼마나 많은 장애인 관객을 만나게 될지 모르겠다. 그저 이 전시를 찾은 누군가에게 우리의 시도가 의미 있게 다가가, 그간 숨겨왔거나 숨겨져 왔던 취약함을 조금이나마 편안하게 드러낼 수 있는 자리가 되길 바란다.

이주연

미학을 공부하고 서울시립미술관 코디네이터, 서울대학교미술관, 국립아시아문화전당 학예연구사를 거쳐 현재 국립현대미술관에서 학예연구사로 일하고 있다. 미술이 보는 사람에게 일으키는 변화, 전시를 만드는 방식과 전시가 말하는 것 사이의 관계에 주의하며 일한다.

이충현

조금다른 주식회사를 운영 중인 문화기획자. 문화예술계 전반에서 접근성 기획자, 교육자로 활동 중이다. 문화기획에는 윤리가 동반되어야 한다고 믿고 있으며, 결과물만이 아닌 그 과정을 잘 만들어내는 것 또한 중요하게 여긴다. 전시 《기울인 몸들: 서로의 취약함이 만날 때》의 접근성 기획을 맡아 함께했다.

Anyone who dares to say there is something “for all” must be prepared to face cynicism. The same applies when one assumes there is a “museum for all.” This does not mean that everyone must enjoy fine art or that everyone should have the same taste. Rather, the phrase questions whether museums are securing their legitimacy as a public space. The issue of “accessibility,” which has recently become a major topic of discussion in the arts and culture sectors, lies at the forefront of this rhetoric.

Since the moment of their inception—when artworks once monopolized by the privileged class were opened to the public during the French Revolution in the eighteenth century—the motto “for all” has served as an ethical principle that public museums are expected to uphold. But this raises a fundamental question: Can the pursuit of beauty truly align with the pursuit of justice? A museum is a place where cutting-edge culture is presented. It is also true that art derives its subversive power, in part, from its ability to transcend questions of right and wrong. And yet no matter how pure the sound of the legendary Emille Bell (Sacred Bell of Great King Seongdeok) may be, can it ever justify the sacrifice of a child’s life? The questions lead endlessly into one another.

On a more practical level, an exhibition is an act of presenting cultural value to society as a form of commodity. Like many other aspects of contemporary society, the concept of putting together an exhibition operates on a calculation that seeks to invest as little capital as possible while extracting as much value as possible. In other words, when the creation of cultural value as profit becomes an extreme objective, ethical shortcomings may no longer seem like pressing concerns. For example, there may be a migrant worker who paints alone every day in order to create a vast exhibition space on a limited budget. To produce a high-quality catalog, one might opt for a skilled printing company rather than one run by people with severe disabilities. A VIP visitor might be offered a carefully designed tour route, while another visitor in a wheelchair is routinely directed to the back entrance without much thought. One may feel sorrow for colleagues who had to leave the field due to declining health or emotional strain, yet still find oneself feeling unjust resentment toward a colleague who steps away from a mountain of work to take care of personal matters—even when the exhibition itself claims to stand for the exact opposite. I am ashamed to admit that I, too, have found myself caught up in some of those same kinds of conundrums in the past.

Had I been alone, examining the issue would have ended up as nothing more than skepticism full of empty words. Fortunately, I had a guide to accompany me on this journey, A Little Different.inc., which helped design the accessibility features of this exhibition by sharing their vision from the early stages of exhibition development. Specifically, the company proposed to develop the exhibition and its accessibility from the following perspective:

The essence of accessibility lies not simply in implementing it as a functional feature, but in enabling people to enjoy content regardless of boundaries. Even while providing accessibility based on functional convenience, it is equally important to recognize that accessibility can also be an act of aesthetic creation.

If the very methods used to enhance accessibility can themselves become objects of appreciation and enjoyment, might it be possible for these two seemingly different goals to meet at some point? After all, changes in the medium are closely tied to artistic expression, and aesthetic sensibilities can both unite and divide us. With this in mind, we set out to explore ways in which accessibility features could not only serve their practical purpose but also become the subjects of enjoyment in their own right.

Furthermore, A Little Different.inc. reminded us of the role an exhibition can play when trying to focus more attention on accessibility features—even if every goal cannot be achieved all at once, it becomes an opportunity to accept limitations and share a common direction. As the company so aptly put it:

Ironically, a “museum for all” must begin with a recognition of the museum’s limitations. It starts with acknowledging that today’s museums are not, in fact, spaces for all; and that with the time and resources we have, we cannot completely dismantle the barriers they hold; and yet it is through this shared understanding and acknowledgment that we find the reason to continue striving toward the goal of a museum for everyone.

If I was able to push past the pressure to be perfect, the fear of unexpected criticism, and the lazy desire to settle rather than risk wasted effort, it was because I had colleagues who stood by me.

In this way, Looking After Each Other was shaped through mutual understanding, compromise, and encouragement between two teams with different perspectives. This essay was written to share that journey. As it was impossible to include every story, I chose three examples—Braille blocks, easy-to-read texts, and audio guides—that effectively illustrate the conflicts and negotiations which arose between the goals (of seeking both useful and enjoyable accessibility tools) and the practical conditions surrounding them. There is no other reason for documenting what may ultimately end in failure. Just as this exhibition owes its existence to the hard work carried out by the many people who wanted to include those once left uninvited, I hope this record will help someone else take one step further in the future and ask new questions in continuing this effort.

Braille Blocks with New Rules

Even the question of whether to install Braille blocks was a matter of debate. The idea of enabling independent viewing for visitors with visual impairments sounded admirable, but at the same time it seemed utterly unrealistic. Moreover, the budget was insufficient to extend Braille blocks beyond the exhibition hall into the lobby space. Was it even possible for a visually impaired person to make their way alone from the nearest subway station or bus stop to the museum? The answer was no. Accusations that the exhibition was just for show echoed all too clearly in our minds. Perhaps, out of fear, we were looking for an excuse not to install the Braille blocks at all.

Exhibition Planning Team: Of course, we do take visitor flow into account when preparing an exhibition. However, viewing is ultimately a matter of personal choice. If Braille blocks cannot be placed along every possible route a visitor might choose, would it not end up restricting, rather than supporting, that autonomy of viewing?

Accessibility Planning Team: Nonetheless, is it not better to allow limited access to the artworks than to provide no access at all?

The answer was clear. The Exhibition Planning Team, together with a spatial designer, began seeking ways to install Braille blocks. We decided to set a goal: to create an environment where visually impaired visitors could move independently, at least within the exhibition hall itself.

Once the decision to install Braille blocks was made, questions arose regarding their design and form. Since the blocks would be installed in an art museum, some suggested that the blocks could become a subject of artistic experimentation as well.

Exhibition Planning Team: Must Braille blocks always be in yellow or white? Are the forms of Braille blocks strictly limited to dots and lines? Can we not use other colors or shapes?

Accessibility Planning Team: The first and most consequential principle of Braille blocks is to ensure accessibility for visually impaired people. Exploring new possibilities is certainly worthwhile, but such attempts must not compromise the fundamental purpose and function of Braille blocks. Therefore, we ask that any creative approaches adhere to the following principles:

- Do not alter the distinct roles of dot and line shapes.

- Ensure that the color of the Braille blocks clearly contrasts with the surrounding floor.

- Do not deviate from the established angle, layout, and installation guidelines of Braille blocks.

Following this guidance, the exhibition installed Braille blocks by respecting their conventional colors, shapes, and methods of installation.

A Little Different.inc went beyond simply explaining the foundational purpose and rules of Braille blocks; they proposed coming up with a creative idea to express the positions of artworks as a core element of exhibition viewing. In fact, they shared a case from Lima, Peru, where in 2023, a new form of Braille blocks was developed and applied to indicate bus stop numbers. Taking inspiration from the Peruvian example, the Exhibition Planning Team collaborated with the spatial designer to devise a unique configuration of Braille blocks that used a combination of dot-type and line-type elements to signal the location of artworks. This raised an important question: Why did the Peruvians once again turn to dots and lines, just as in conventional Braille blocks, instead of departing completely from established forms? It was due to a practical reason—producing entirely new shapes of Braille blocks would have required a significantly higher budget.

-

Linear Blocks

WhiteThree long, raised vertical lines are aligned in parallel. These blocks indicate that it is safe to move in the direction the lines are pointing.

-

Dot Blocks

WhiteThere are nine blocks with raised circular dots. It signals that you should stop, as there may be a wall, entrance, exit, or the end of a path ahead.

-

Artwork Blocks

YellowThis block has a single raised horizontal line in the center. It indicates that there is an artwork located in front of it.

-

Conversational Audio Guide Blocks

YellowLike other Artwork Blocks, this one features a single raised horizontal line in the center, with four raised circular dots at each corner. It indicates that the artwork includes a conversational audio guide.

Easy Texts or Easy Exhibition Texts

There was no disagreement about the idea that all texts in the exhibition should be written in an “easy” format. This stemmed from past experiences of having visitors feeling disheartened by exhibitions where the texts were so difficult they felt more like monologues than communication, and from a belief that even complex messages could be conveyed through simple language. However, in the context of easy texts, the meaning of “easy” extended beyond the mere difficulty level of sentences. It reflected an attitude concerning the right to know, that is, the belief that no one should be excluded from access to information. With this mutually agreed upon understanding, the decision was made to present easy texts that were not juxtaposed with the museum’s original texts, but as standalone content. Based on the museum’s texts, A Little Different.inc. and artist Choi Seowoo translated and rewrote the material into easy-to-read versions that were then reviewed by the artist and a consultation group of individuals with developmental disabilities. Readability was also enhanced by using a universal font and large-sized text.

The challenge lay in differing views on what constituted “easy” text. For example, the final part of the exhibition’s preface was revised as follows:

Exhibition Planning Team: The exhibition explores ways of seeing diverse bodies as they are, ways of living together with different bodies, and reveals us as beings who lean on one another. If such a sight appears beautiful, we hope that it will be a moment when our hearts grow a little bigger. →

Accessibility Planning Team: The exhibition conveys how to see bodies as they are, how to live with many kinds of bodies, and how to become people who can lean on one another.

The final sentence (i.e., “If such a sight appears beautiful …”) was the part we deliberated over until the very end. It was not something one could call “difficult,” but it was also not a clearly stated phrase in that its meaning only emerged upon reflection and repeated reading. Yet because it had been written with the intent to gently prompt contemplation in the reader, we could not help but feel a sense of regret over the decision to remove it.

After that, we were overwhelmed with thoughts about writing in easy language. To what extent can the complex context and intentions behind an exhibition or artwork be conveyed through simplified language? In a museum, a place that speaks of beauty, is it truly desirable to overlook the delicate nuances of language? In a place that invites thought, is it appropriate to offer writing that leaves no room for interpretation or questioning? After all, in the context of a museum, is one’s own aesthetic sense not in fact one source of information for them? From an ethical point of view, is it right to assume that those who demand easy texts lack the ability to infer meaning or to appreciate the delicate nuances of language? While an ideal form of writing which is both easy and beautiful does exist, the path toward achieving that remained distant and uncertain.

Amid the flood of questions, A Little Different.inc reminded us of the guiding principle in this situation: even in easy-to-read texts, no one should be excluded. This was not because people who seek accessible information lack ability, but because among them are certainly those who find inference and interpretation difficult. That being said, since the original texts produced by the museum had already been written in relatively accessible language, the Accessibility Planning Team proposed choosing between the following two directions:

- Preserve as much of the original text as possible, while breaking down difficult vocabulary and long sentences. = Easy exhibition text

- Uphold the principles of easy-to-read text, while inserting key questions (to prompt thought or inference) into otherwise closed sentence structures. = Easy exhibition text

For this exhibition—and under the goal of expanding the right to access an exhibition—the second approach was adopted. Even after this decision was made, discussions continued. While some artists expressed polite discomfort, feedback from the group of individuals with developmental disabilities indicated that the texts were still difficult to understand. As both a stance and an ongoing commitment, our concerns regarding truly easy exhibition texts will, I am sure, continue to linger in the future.

Audio Descriptions as Shared Appreciation

The museum’s budget was not sufficient to assign a dedicated staff member to accompany each visually impaired visitor. Nevertheless, some form of artwork description had to be provided. Although a selection of works could be chosen for audio descriptions, the method of delivery posed a challenge. Using a location-based app was considered, but the sensors lacked precision. At the same time, the exhibition space itself would inevitably be filled with a variety of sounds arising from the artworks and from visitors. Overlapping audio could easily become overwhelming or unpleasant. Headphones, too, were far from a perfect solution. The very requirement to wear them could become yet another burden. This raised two new questions: Could audio descriptions be developed into content that was worth experiencing in and of itself, and serve as a meaningful tool for appreciation even for audiences without visual impairments? And in what ways should the audio descriptions designed for visually impaired audiences differ from the audio guides that serve as substitutes for docents?

Starting with such concerns, A Little Different.inc suggested producing audio descriptions through a slightly different approach. The idea was to pair two individuals (one of whom would be a visually impaired person) to have a conversation about a given artwork. Based on that exchange, the audio description would be created. There were several reasons for this method. First, it allowed for easier identification of questions that arise from the actual perspective of someone with a visual impairment. Second, it aimed to provide an artwork description that was both relatable and vivid, as well as shaped through individuals’ appreciation. However, to address concerns that such dialogues might veer too far into irrelevant personal detail, the team decided to exclude any content unrelated to the artwork itself. In addition, the audio description included various elements that generally accompany the appreciation of artworks in a museum, such as the atmosphere of the exhibition space, scents, echoes, sounds, tactile sensations, and the order of experiences. This revised format in creating audio descriptions was intended to demonstrate that appreciating artworks in a museum involves more than just sight, allowing both visually impaired and non-visually impaired audiences to share their experiences through various senses. Furthermore, not all people with a visual impairment experience an exhibition in the same way. Given that individuals with low vision, for example, still rely heavily on sight as part of their experience, the audio descriptions could reveal differences in sensory engagement depending on how one uses their sensing organs. The following is an excerpt from one such audio description.

Accessibility Planning Team:

A: The artist’s name is Christine Sun Kim. Let me look her up. It says here that Christine Sun Kim is a Korean-American artist who was born deaf.

B: Ah, so is that why she creates her artwork by using the sign language that she communicates in?

A: That seems to be the case. And if so, perhaps the message she’s trying to convey is something like, Those who sign and those who read sign language may be looking at different sides of the hand, but the meaning still comes through the same.

B: It’s quite possible. Come to think of it, Braille is read in a single direction, since it is printed on a flat surface, whereas sign language, being a language that uses the body, specifically the hands, can be perceived from multiple angles.

A: Oh! I never thought about it that way. That makes so much sense. Actually, I’ve been thinking about learning sign language myself.

B: Really? It took me such a long time and so much effort just to learn Braille. I wish I’d started learning Braille when I was younger … Trying to learn it as an adult was really difficult.

The explanatory texts produced by the museum aim to describe, interpret, and evaluate artworks as objectively as possible. In contrast, this audio description clearly moves in a different direction. Regardless of where this audio description may lie on the spectrum between objective description and subjective appreciation, however, there seems to be something fundamentally beautiful in it. The reason is not entirely clear, though. Perhaps it is because if art has an essential purpose, it lies not in the act of looking at something, but in the act of sharing and communicating something with others.

The sentence “accessibility is an aesthetic act of creation” serves as a kind of mantra for the Accessibility Planning Team. As anyone who has read this far will have sensed, working on accessibility is a continuous process of persuasion and compromise. In order to become a “museum for all,” one must first strive to be a “museum for just one.” That means pursuing a certain value that is not backed up by numbers. Because such a value has no clear answers, the pursuit has no end. And work that defies quantification is often met with doubt.

Should Braille blocks be installed even if they cannot guarantee complete freedom of movement? Is creating Braille blocks in a new language system urgent or effective enough to warrant significant investment? How can we write texts that are not only easy enough for everyone to understand, but also great in the delicate nuances of language? Can a viewer’s appreciation, rather than an artist’s explanation, serve as a meaningful interpretation of an artwork? Must people with disabilities prove their disabilities in order to book accessible tickets? Upon asking all these questions, how can we begin to speak of what comes next, when so many are still being left out?

Amid these countless questions and ongoing discourses, the sentence “accessibility is an aesthetic act of creation” has served as a guiding light that continues to provide momentum for all who work in museums. We thought long and hard about the meaning of this beacon-of-light statement with those who joined us on this journey, and we pursued it with great effort. Of course, there are still questions for which we have not found answers (we may even have more questions than before we started) and there were moments when we had to make compromises for various reasons. Still, we do not believe that compromise is necessarily bad. Even if saying “this is as far as we can go for now” may sound like a form of complacency or defeatism, it can also be a resting place for the time being—a way to keep looking forward and building something sustainable. After all, this is not the end. We want to do better next time, especially in areas where we previously fell short.

We do not know how many visitors with disabilities will come to see Looking After Each Other. We simply hope that our attempt will resonate with those who visit this exhibition, and that it will become a venue where they can feel comfortable revealing even a small part of the vulnerabilities they have hidden or that have been hidden away up until now.

Lee Jooyeon

With a background in aesthetics, she has worked at Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul National University Museum of Art, and the Asia Culture Center. Now a curator at the MMCA, she focuses on how exhibitions speak and how art transforms its viewers.

Lee Chunghyun

As a cultural organizer and educator, he runs the organization A Little Different Inc. Active across the arts, he specializes in accessibility. He values the ethical dimension of cultural events and gives importance to the process as much as the outcome. He led the accessibility planning for the exhibition Looking After Each Other.